[ Sources ] [ Links ] [ Reconstruction ] [ hist14 class homepage ]

Final Project for History 14 - The Worlds of Leonardo da Vinci, by Taqi Jaffri and Justin Grosslight. Click the link above for pictures of our reconstruction of Leonardo's short focal lenght lens grinder.

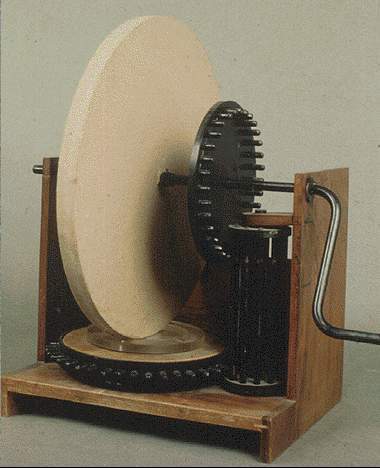

Reconstruction of Leonardo's small focal length lens grinder.

http://www.museoscienza.org

Did Leonardo da Vinci Use Concave Mirrors?

In his Codice Atlantico, Leonardo offers two of sketches of mirror making machines. One machine is designed for grinding concave mirrors of small focal length. The other machine, a much larger piece to implement, grinds mirrors of large focal lengths. Though Leonardo da Vinci creates sketches of mirror grinding, one crucial and logical question to ask is whether he used such mirrors in his artwork or drawing. On this subject, a bevy of scholarly research has surfaced both proclaiming and refuting da Vinci’s use of concave mirrors and lenses.

Of all the scholarly research debating whether Leonardo used concave mirrors, David Hockney emerges as this thesis’ strongest advocate. Hockney’s argument is as follows: Renaissance artists use a process called focusing, whereby a bright light enters a dark room through a small opening. Light enters the room and refracts through a lens at the small opening, thereby projecting itself onto canvas opposite the light’s entrance. The real life image wishing to be painted stands outside, while its image projects onto the canvas. In the case of focusing, images appear inverted. Mirrors were employed in a similar fashion.

Focusing itself gives newfound qualities to painting and drawing. Most importantly, it can magnify images, thus allowing an artist to construct details otherwise difficult to draw with the naked eye. Moreover, such projections, “compress a scene’s complex, three-dimensional masses, gradually giving light and color into clear, two-dimensional shapes whose outlines can be quickly and confidently traced” (Carrell, 78). One major drawback, however, is that light is lost through projection, ultimately increasing contrast. Colors dim, and an artist’s palette becomes composed of, “deep, rich tones” (Carrell, 79). Through focusing a new world of images emerges.

In support of his argument, Hockney gives examples. Hans Holbein’s The Ambassadors (1533) makes a strong case for use of lenses. Careful analysis of this work reveals that Holbein’s object in the bottom center of his work is really a human skull. Similarly, Hockney remarks that the details on the globe in the painting are incredibly accurate. Magnifying the painting, one sees the letters “AFFRICA” painted on the African continent. Not only this, but the African coastline is clearly outlined and minor geographical features are names. Similarly, the shape on the foreshortened lute is very difficult to paint with the naked eye. When asked if an artist could eyeball such precise figures, Hockney boldly asserted, “No way, absolutely no way that could have been eyeballed, no way mathemtical perspective could account for such percision” (Weschler, 74). It appears lenses are a necessity for creating Holbein’s work.

| Hockney’s argument furthers through Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding (1434). In this piece, one can clearly see a convex mirror in the center background. Additionally, the details in the mirror appear so precise that they would almost require optical instrumentation assistance. Of crucial importance, however, is the convex mirror. If convex mirrors could be made and silvered, then it is highly plausible that the reverse, a concave side, is likely silvered to construct a concave mirror. Hockney does not stand alone in his argument. Fellow academician Charles Falco also argues his point with concave lenses. In the eyes of Falco, mirrors and lenses shared analogous properties. It is rather apparent by the era of Galileo, that astronomers had the ability to use lenses and create telescopes, but even in Leonardo’s epoch this is the case. Falco points to Raphael’s Pope Leo X (1518). In it, the pope has a pair of spectacles in his hand; these spectacles look as if the lenses are concave, which is necessary to enhance vision. Raphael’s painting provides visual proof for our claim.

|

Fig. 1 Jan van Eyck’s Arnolfini Wedding (1434) |

Through the practice of focusing and refocusing, Hockney finishes his argument with a discussion of Lotto’s Portrait of Husband and Wife (1543). In this piece, Hockney argues that the piece’s greatness is characterized not by its perfections but rather by its distortions. Scrutiny over Lotto’s work shows that the diagonal line to the right of the yellow keyhole image on the tablecloth is off by three degrees as the line recedes from the foreground of the work. Such a linear deviation seems erratic and likely reflects the use of a lens to attain accuracy.

Stanford professor David Stork offers perhaps the strongest evidence against lens use. Stork shatters Hockney and Falco’s arguments by remarking that if indeed lenses were used, then upside-down brush strokes on some Renaissance painting must exist. Such is not the case. On the other hand, many paintings evince a surprisingly large number of left-handed subjects; left handedness was not the most benign of traits in the fifteenth century and was often thought to correlate with diabolical tendencies (Gorman). Historian Michael John Gorman, however, offers an alternative method, whereby concave mirrors and lenses are used to produce an erect image on canvas. To argue his point, Gorman turns to Renaissance playwright Giambatista Della Porta. Della Porta creates a system whereby images can stand erect. In his work, Natural Magic, Gorman Quotes Della Porte:

But if you wish for the images to appear upright, this will be a great feat, attempted by many but not discovered by anyone until now. Some [perhaps Della Porta is referring to Benedetti] place flat mirrors at an oblique angle near the hole, which reflect an image onto the screen opposite that is more or less upright but dark and confused. We, by placing the white screen at an oblique angle to the hole, and looking towards the part facing the hole, saw the images almost erect but the pyramid [of light] cut obliquely showed the men without any proportion and confusedly. But in the following way you will have what you desire. Place an eyeglass made from a biconvex lens [specillum e convexis fabricatum] in front of the hole. From here the image falls on the concave mirror. Place the concave mirror far from the centre [i.e. from the focal point of the lens] so that the images which it receives inverted it will show upright, because of the distance from the centre. In this way, above the hole on the white paper you will see the images of the things which are outisde so clearly and openly that you will never cease to be delighted and amazed. But here I should warn you, so that you don’t waste your efforts, that it is necessary for the lens to be proportioned to the concave mirror, but, as you will see, here we will speak of this many times.

Gorman then depicts an image of Della Porta’s system, whereby objects stand erect. Thus, a proper combination of a convex lens with a concave mirror arranged with suitably proportioned focal lengths, permits clear, large, and upright images to be projected. Before Groman’s thesis, Della Porta’s remarks were unaddresed by Hockney, Falco, or their components.

One roadblock still exists: Leonardo’s death antedates many of our examples of concave lens and mirror usage. Professor Michael Gorman remarks that Johannes Gutenberg, in the 1430s, created a series of handheld mirrors – Heiltumspiegels - designed specifically for pilgrims. Pilgrims would use mirrors to retrieve images at their mecca and them display them to their friends back home on the dark, greenish surface of the mirror (Gorman). Dr. Gorman also remarks that Leon Battista Alberti, in his treatise, On Painting, tells his audience that, “A good judge for you is the mirror. I do not know why painted things have so much grace in a mirror. It is marvellous how every weakness in a painting is so manifestly deformed in a mirror. Therefore, things taken from nature are corrected with a mirror. I have truly recounted things which I have learned from nature” (Gorman). Fillipo Brunelleschi, with his invention of perspective in 1425 and his designing of the Baptistry used a plane mirror to aid his work. Even in Leonardo’s day, there was heavy documentation and application of mirror usage.

The crucial question, of course, is whether Leonardo himself used concave mirrors or lenses in his work. With respect to painting itself, Leonardo only completed a handful of works thereby limiting our evidence; it seems premature to definitively postulate an answer. Signs, however, support usage. Other symptoms of Leonardo’s reveal that he had a strong sense of graphical powers of lenses and mirrors. After all, Leonardo did write backward and from right to left in his notebooks; he found this to be a relatively easy and common task. Moreover, an entire section of his notebook is devoted to optics. Leonardo also writes:

...making glasses to see the Moon enlarged... and ...in order to observe the nature of the planets, open the roof and bring the image of a single planet onto the base of a concave mirror. The image of the planet reflected by the base will show the surface of the planet much magnified (Art and Optics).

As well as,

When you wish to see whether the general effect of your picture corresponds with that of the object represented after nature, take a mirror and set it so that it reflects the actual things, and then compare the reflection with your picture, and consider carefully whether the subject of the two images is in conformity with both, studying especially the mirror. The mirror ought to be taken as a guide – that is; the flat mirror – for within its surface substances have many points of resemblance to a picture; namely that you see the picture made upon one plane showing things which appear in relief, and the mirror upon one plane does the same, the picture is one single surface, and the mirror is the same. (quoted in Goldberg, 1985, p. 152) (From Gorman)Clearly, Leonardo both understands the concept of a concave mirror, mirrors in general, and the importance of mirrors in painting.

Regardless of whether Leonardo created artwork with mirrors or lenses, it would seem reasonable to assume that he had access to such objects, especially considering his social circle. In 1469 he was apprenticed to the famous artist Verrochio; thirteen years later he was present the court of Ludovico il Moro in Milan. In 1502, Leonardo entered the service of prince Cesare Borgia, and in 1516 he received an invitation from the King of France, François I. Da Vinci also commissioned famous paintings for famous women: cases in point are his portraits of Lady Genevra, Cecilia Gallerani, and the Mona Lisa. Since Pope Leo X had access to lenses, it is more than certain Leonardo’s cohort likely did too. Leonardo’s innate curiosity likely led him to inquire on such lenses, and likely employ them in a drawing or painting.

Many art historians and historians of science are very curious to find conclusive evidence of whether Leonardo did indeed employ lens and mirror techniques. Our professor at Stanford, Michael John Gorman, is one such individual. Both of us would like to thank Dr. Gorman for opening our eyes to a new perspective on art and science, and for linking two seemingly disparate disciplines together. Studying under your Dr. Gorman’s directive has been a truly wonderful and lively experience.

please visit the links page for more information

See Justin Grosslight and Taqi Jaffri’s replica of da Vinci’s

Mirror Grinding Machine

(small focal length grinder model)